(The

Editor, in writing this booklet, has attempted to make this a historical

record of the activities of this ship and yet make it of such human

interest that all to whom it is dedicated will, months and many

years from now be able to read through it and remember those days

when we served together and each and every man, be he with gold

or nothing on his sleeve, felt and considered himself equal in

the battle against a common enemy. To

date our task has been “well done” and in appreciation

of the services all hands have performed, I pass this story on

to you. JHB).

HISTORY

The

U.S.S. PHILADELPHIA, a light cruiser of 10,000 tons, was built

at the Navy Yard, Philadelphia, Pa. and

placed in commission on the 23rd day of September, 1937. A

sister ship of the BROOKLYN, BOISE, SAVANNAH, NASHVILLE, HONOLULU,

and PHOENIX, this vessel

joined the fleet during the latter part of 1937 after a brief shake-down

cruise to the Caribbean.

In

1939 she was transferred to the West Coast and remained in the

Pacific area until May, 1941 when secret orders were received sending

her through the “Big Ditch” to the Atlantic Theater

of operations and regular convoy duty.

To

those men who were on the PHILADELPHIA during

those cold, dreary and hectic days while enroute to and from Iceland, Scotland and

other ports of call in the eastern Atlantic,

many vivid experiences will remain. The

unending periods of submarine alerts, the long cold watches on

deck after which one took ten to fifteen minutes in removing clothing

in order not to thaw out too quickly, the joy of heading back home

and the ultimate thrill of again setting foot on our own native

soil are some of the things that will never be forgotten.

And

then the war made the task of this vessel a much tougher one. While it steadily plowed its way across the

rough waters of the north Atlantic the “gold-braids” were

making their plans and in those rough notes a small but important

spot had been set aside for this fighting man-of-war.

The

first inkling that this vessel’s crew had of any major plans

being put into effect was obtained during September—October,

1942 when the ship was sent to the Chesapeake Bay area

to maneuver and practice intensively for weeks with other units

of the fleet. Amphibious

landings, long the dream of officers in the Army and Navy, were

rehearsed until all hands were well versed in all phases of operations

and capable of taking care of almost any emergency which might

arise.

During

the middle of October the task force, comprising hundreds of vessels,

left the Norfolk area

to cross the Atlantic. Only after some distance out at sea were all

hands notified of the extent of operations to be undertaken, the

necessity of accomplishing the landings as quickly as possible,

the opposition expected and the gigantic size of the convoy crossing

at that time. For miles around and as far as the eyes could

see there were ships all headed for North Africa. The battleships, cruisers and destroyers were

ever on the alert for any hostile vessels or aircraft and a constant watch was kept to intercept any submarines

or other vessels which might have been in a position to intercept

the force or to furnish information to the Axis High Command as

to the movements of the task force via radio signals. Every precaution

was taken and that they were sufficient was proven by the fact

that no full scale opposition was met until. all ships had arrived

at their appointed destinations. This vessel assigned to the Safi,

French Morocco area, met with very little opposition. In addition to some destroyers for patrol work,

the battleship NEW YORK had

been made a unit of this force. The

landings were successfully carried out, the little opposition put

up by the opposing forces quickly overcome, and this ship's return

to the Navy Yard, New York, N.Y. for a 10-day overhaul quickly

effected.

Two

quick convoy trips to Casablanca,

French, Morocco,

with time off on each side of the Atlantic,

made the time go by very quickly. The

short periods at sea were soon forgotten especially after a few

days in port. In March of the present year, the vessel again

returned to the yard at Brooklyn for several weeks during which

time many improvements were made; improvements which were to have

tremendous effect on this ship’s defenses, especially for

the type of duty to which it had been assigned.

The Casablanca conference

which had brought together Churchill, Roosevelt and

the heads of the armies, navies and air forces of most of the United

Nations had been held and the plans for the next campaign were

well in the process of execution. The actual landings, dates on which effected,

places, forces involved, etc. were all secret but before these

could be carried out a great deal of work was to be done by all

units taking part in the operation.

The

second period of training in the Chesapeake indicated

that a major movement was underway. Intensive

training for a period of over five weeks—periods during which

men who had just reported on board but a few weeks ago were being

assigned to important battle stations. And

then—the signal to return to Norfolk, VA to

await for their orders.

Still

short a number ratings, the vessel requested an additional amount

of seamen to be transferred prior to its departure from that area. About 250 men reported on board during those

last few days; new men, just out of training stations, young boys

of 18 and 19, untried, bewildered by the sight of all they saw

as they reported aboard, glad to be on a real “man-of-war” at

last. And then, as they

became accustomed to the ship, the strange talk of the older men

on board, the requisites of each man with regards to his body his

duties, and his stations, the story of the ship’s history;

then was it possible to see the difference in these youngsters

who but a few days ago had been in “boots in training”. The

feeling of pride and the zeal with which the new men took to their

new duties augured well for the ship and had an omen of ill tidings

for any enemy to be encountered.

The

group that sailed from Norfolk during

the early part of June was not a very large one. The crew aboard this vessel as a whole knew

and felt that something was coming off but the size of the convoy

indicated that it was only a small operation to be undertaken. And it was not until after the task force had

been safely birthed at Mers-el-Kebir, Algiers on

the 22nd of that month that it was possible to get a

better picture of the shape of things to come.

Mers-el-Kebir

was overflowing with vessels of all the allied navies. The many thousands of soldiers always on the

move was also a definite indication that something very big was

soon to break. When all

communications between ships in the harbor and the beach were stopped

on the 28th of June, it was a very definite sign that

it would be only a matter of days before the operation was carried

out.

To

keep the Axis High Command in a quandary as to the actual landing

places, the allied leaders had planned very thoroughly. The

numerous task forces which deployed from the main transport groups

had even some of our own units confused as to just where they were

headed. This vessel was one of those task forces which

left Mers-el-Kebir on the 5th of July, proceeded towards

the coast of Sardinia, tracked back to the

east of Malta and

then picked up the regular troop convoys to the west of that famous

lime-stoned island fortress and landing field.

Scoglitti:--searchlight

displays; fires ashore; thunderous roar of bombs; sudden quiet;

those moments of suspense -- the firing on prearranged targets

ashore, and then -- the long period of waiting. Waiting,

wondering, hoping, praying. Every

moment expecting something, anything to happen. The

anxiety of expecting good news of landings successfully accomplished

was nerve-wracking and when no news was to be had even the firing

of guns ashore broke that period of inactivity, of standing by

waiting for something to happen.

And

then at last the news that one landing had been effected and another

and still a third until reports came pouring in that very little

opposition was being met and that all beach heads had been firmly

established. The spell had been broken just in time and

the crew was able to relax -- but not for long for the Luftwaffe,

no doubt aroused from its lethargy a short time after the original

landings had been made, was already winging its way towards the

seen of the action.

That

first enemy bomb landed about 35 yards off the port bow and really

gave this vessel its first baptismal under enemy attack with a

shower that wet down all hands on topside and those that escaped

the drenching felt the concussion of that missile which was addressed

to the PHILADELPHIA but was delivered to the wrong door.

The

days of Scoglitti were hectic ones. They

were the trying periods for most of the crew as few men had been

forced to undergo the trying rigors of constant and repeated air

attacks by hostile planes operating from nearby land bases. Yet

with the success of the landings at Scoglitti and the numerous

other beaches in the southeastern portion of that highly-touted

and impregnable Axis fortress, the job had only started.

On

the 15th, just five days after the initial attacks,

the PHILADELPHIA pointed

its bow westward and as it steamed past the port of EMPEDOCLE and

the city of Agrigento nestling

peacefully against the hillside further inland, the crew sensed

that a momentous job was on hand. The

pummeling of these two strong points by the ships batteries in

order that these important centers be taken as soon as possible

and permit the army to proceed unhindered towards the west and

north had to be carried out. The perfect road and railroad networks extending

from Agrigento were

very important to the army at this stage of the game and it was

an absolute “must” that these two points be forced

to surrender as soon as possible. The crew aboard this vessel turned to with

fervor and for more than 12 hours the gun crews laid salvo after

salvo and when “cease firing” was given, over a thousand

rounds had been dropped in areas of selected strong points. When

Porto Empedocle and Agrigento surrendered

to the small unit of rangers which marched in the next day all

hands on the PHILADELPHIA felt

proud of the work performed the previous day. Yes,

even the German “supermen” were finding it hard to

stand up against the terrific fire of these little barking dogs

that this vessel aimed at them.

Back

to Gela and roaming

the southern coast of Sicily and

then Bizerte. On the 22nd of July was celebrated

the first liberty in Algiers. The tension had been eased and it was a relief

to set foot on dry land again after a month on board ship. Only a few days of relaxation though and enroute

again. Palermo ahoy!

The

Casino - wrecked shipping - the water front with the large ship

in the street - the acres of buildings devastated by the bombers

of the allied forces were all a part of this city which had once

been the home of kings, now a fallen prey in the path of General

George S. Patton Jr. and his now-famous U.S. seventh army. Palermo,

laid to waste by some of the most accurate bombing raids the world

has ever witnessed, its population scattered throughout the surrounding

hills, its transportation facilities wrecked and inoperative, still

retained its majestic serenity even though it was the peace of

death. The quietude prevailing throughout the area as this ship

steamed into the harbor and noisily dropped its mud-hook just outside

of the large man-made outer mole was disconcerting. The inactivity onshore gave one the gruesome

feeling that life in the city did not exist, a feeling broken every

so often by the appearance of small whiffs of smoke indicating

that fires started many days ago were still burning.

A

few hours after the arrival of the PHILADELPHIA at Palermo,

that city appeared to have become alive again; the movements of

the small army units, activity of small vessels in the harbor,

the traipsing of people along the waterfront, the varied pitches

of airplanes as they whizzed overhead. Each of these in its turn attracted the attention

of the men aboard the ship as they lazily perused and listened

to the scenes before them.

But

inactivity for these stalwart fighting followers of the sea was

not on the schedule and on the last day of July the “GALLOPING

GHOST OF THE SICILIAN COAST” as the ship had now been nicknamed

steamed east to immobilize the Axis gun emplacements to the rear

of their lines, prevent the enemy from planting mines in its retreat

toward Messina and disrupt his lines of communication as much as

possible. Taking her assigned

station in the fire support area, the PHILADELPHIA opened fire

on artillery, troops, bridges, trucks and tanks designated by the

vessels spotting planes which had been catapulted to spot and pick

up targets for the firing.

Even

as the mighty cobra often finds its nemesis in the small but ever

watchful mongoose, so this vessel almost found itself mortally

stricken by those little flying devils of the Luftwaffe as they

circled, glided and dive bombed the ship after it had been shelling

the German positions for approximately six hours. The nearness of those shells which had been

fired by some shore battery at the PHILADELPHIA earlier in the

morning was soon a thing of the past; the rigging that had been

torn away by one of the enemy projectiles which had landed but

a mere 20 feet abreast five-inch gun No. 4, the numerous shrapnel

holes bearing grim and mute testimony of the accuracy of the Axis

fire and the three wounded men lying in the sick bay -- all were

to be pushed back in the memory of time at that moment as the planes

overhead came in and made their attacks, dropping their lethal

loads uncomfortably close to the ship. Repeatedly,

despite the deadly hail of bullets spouting from the AA batteries

of the cruiser, the Luftwaffe pilots closed in and let go their

messengers of death and destruction and only through the goodwill

of the Divine Providence did the ship manage to get out of that

area and back to Palermo safe and sound except for a number of

thorough drenching and heavy shakings-up.

What

a blessing it seemed to all hands that afternoon as we arrived

at Palermo. It was with a feeling of relief and security

that the crew turned in that night, safe in the belief that here

at last one could find peace and quietude within that ever so slight

margin of distance which meant safety from air attacks and bombings.

The

rude awakening from that peaceful sleep as scores of flares lit

up the city and harbor of Palermo,

quickly followed by the heavy detonation of bombs throughout the

entire area suddenly brought home to each and every man aboard

the PHILADELPHIA that

they were really in the front yard of the Axis.

The

suddenness of the attack, the lucky hit of a bomb in an ammunition

dump where gasoline was stored quickly exploding and lighting up

the port area for a distance of three to five miles, the burning

coastal vessel, the hurried departure from our anchorage under

a straddle of bombs on the bow and the constant rumble of bombs

as they dropped all around the area; incidents, only passing incidents

all jumbled together in the minds of the men aboard this ship as

they carried out their duties mechanically repaired to their stations

quickly manning the guns and blazing at the hostile planes which

had sneaked through to accomplished the mission which had been

unsuccessful the preceding day.

Fifty

or so planes were estimated to have made the attack but a number

of them never returned to their bases in nearby Italy. Despite the brightly lit harbor which made

bombing of vessels in the area a very easy operation, the enemy

planes were unable to make any direct hits on the ships which were

sending up a deadly hail of bullets at all planes in their vicinities

preventing the Axis fliers from coming down too close for accurate

bombing.

It

was true that the PHILADELPHIA had

relaxed that night but the lesson learned was not a very expensive

one. The damage caused during that raid was not extensive although

it turned out to be one of the most brilliant exhibitions of A.A.

fire, bursting bombs and conflagrations ashore yet witnessed by

most of the people aboard the ships in the harbor. The

necessity of being ever on the alert, being prepared at all times

to combat any form of attack, making the utmost use of all of the

offensive and defensive equipment on board; those were the lessons

learned during that eventful day and night.

Those

21 days on the North Coast of Sicily will long live in the memories

of all hands who went through those three “leap-frog” landings

enabling the U.S. 7th Army to bring the Sicilian campaign

to a very quick end and permitting that force to be the first to

reach Messina. Those repeated

missions up the coast to San Stefano, then Cape D’Orlando

and suddenly the collapse of resistance in that area with the resultant

bombardment of Milazzo; that night spent in running down the Italian

cruiser force which was expected to make an attack on Palermo;

that peaceful mission another night when the admiral decided to

bombard the city of Messina and plans were changed at the last

minute when reconnaissance planes were picked up after spotting

the ship and the aircraft headed back to the bomber base possibly

to bring out a strong force of bombers; the numerous bombings,

near misses, and the resultant bringing down of eight enemy planes

definitely credited to this ship with numerous other “possibles”. All

were “scenes” in the last act of the Sicilian campaign.

Yes,

the days were hectic ones. The

day consisted of 24 full hours. No

one made any real attempt to keep track of the actual dates. There were many times when it appeared almost

impossible to tell whether it was day or night as those flares

dropped by enemy planes lit up the sky, silhouetting the ship being

repeatedly bracketed by bombs. The

days rolled along, everybody yearned for a rest but as long as

a job was unfinished it was realized that this gallant vessel would

have to be present to prove to the German High Command that the

spirit of the U.S. navy as exemplified by this one fighting man-of-war

would not and could not be broken despite the very best that the

Axis could send out to destroy the PHILADELPHIA. Even the E -boat attacks, apparently believed

by the Nazis to be the one thing which the allied forces could

not overcome, were frustrated by the excellent work of the outer

screen of destroyers. The spent torpedoes found floating around the

Palermo area on the following day were indications of the work

being done by the Germans, i.e., to expend their torpedoes or bombs

as quickly as possible even though no targets were present, and

thus make a hasty retreat to their home bases. That

big day while operating off Cape Calava when

eight FW-190s of the b Berman Goering squadron made that sneak

dive bombing attack which appeared to have been a suicide attempt

to get the PHILADELPHIA will

long be aflame in the fires of our thoughts. Three of the attacking planes were brought

down by this vessel’s A.A. fire, one by an accompanying destroyer

and a fifth by the fighter planes covering this vessels maneuvers. Two others were believed to have been damaged

and were last seen heading back toward Italy in

a trail of smoke. A high

price -- seven out of eight.

Yes,

all of these things plus the hundreds and thousands of other incidents

which occurred throughout various stations of the ship will bring

back to the crew of this mighty warship memories of those days

off Palermo. And to have been the only cruiser in that area

for the entire period will always be something to talk about. And that this ship had been in the first U.S.

task force to bombard the mainland of Italy during that special

night mission with all hands on their stations awaiting that expected

shower of bombs; of all this could the entire crew be proud of. Yes,

a job had been finished and from all reports it had been well done.

No

tears were shed on the morning of August 20th as this

vessel steamed around the point and left Palermo astern,

its long nose pointed on a westerly course and thence towards Bizerte. The next day was a busy one but the work performed

was of a nature more to the likings of the men on board for supplies,

ammunition and fuel were being received. Fresh

meats, butter, flour, coffee and all of the other delicacies of

which the ship was running rather low.

Algiers and

those days of true relaxation again. Movies

on the main deck aft. The

opportunity to go ashore and do the things that one had been looking

forward to. Four days of

peace and a life of ease ashore or aboard. Forgotten

already were most of the hardships which had been endured, the

fears that had gripped both men and boys, the splendid performances

on the parts of all hands.

Four

days in the famous French Algerian port was all that the crew wanted

and needed, for by now it was apparent that another operation was

coming up and all hands were anxious to get going on this new plan,

the ultimate success of which might assure them of getting home

sooner. And as most of the

boys had not seen their loved ones since the latter part of April,

they were most anxious to finish this job and again sit down and

have a few minutes of peace with those at home.

Mers-el-Kebir

with its cluttered harbor, the dingy houses, the scraggly beaches,

its “stadium”, the swimming parties to the west, the

long dusty road leading to the main highway where one caught the “express” to Oran;

all these again brought back memories to the men aboard the PHILADELPHIA. Thoughts of previous days in the same “whole”,

time spent in standing by waiting for the final plans to be formulated

and for preliminary units to move up to the front and that ever

present feeling that another “D” day could not be very

far off.

September

5th and that second departure from Mers-el-Kebir. Enroute again and as on that first journey

the destination was a secret; Crete, Greece, Italy, Sardinia or

the Balkans? Instead of

revealing the ultimate landing point as had been done in the past,

the captain withheld this information until after the ship had

picked up two SOC planes at Bizerte and

many miles were left astern. Landings

to be effected in the Gulf of Salerno,

just to the south of Naples, Italy! Many hearts skipped a beat as that information

was passed out by the “Old Man”. A

quick review of the exact location of this area revealed to most

of the men that it was approximately 160 miles from our closest

air fields. The memory of those bombs falling all around

the ship, the many narrow escapes, the seconds, minutes and hours

spent evading those gnomes of the air, so swift and relentless

that at times it was believed impossible to carry on any longer;

all was brought back into vivid relief in the minds of those men

as they stood on the fantail listening to the captain’s talk. Nothing

was withheld from the men: the

seriousness of the opposition to be effected, the sizes of the

forces to take part in the various landings, the then-known strength

of the enemy and above all the absolute necessity of this vessel

doing its full share in bringing about the ultimate success of

the entire plan; all was revealed and accepted by the men with

no trace of fear for as the talk had progressed, the confidence

of the Skipper that the crew, with two campaigns already under

its belt would come through, and the completeness of the entire

strategy indicated that chances of success were better than average.

Nothing

could have changed the picture of the entire campaign anymore than

that announcement on D minus one day that at 6:15 in

the evening an important announcement would be simultaneously broadcast

from Rome and Algiers.

The radio receivers on board ship were all tuned in on those two

stations but through some phenomenon of nature, not one of those

broadcasts was picked up. The result of that experience made many

of the older men aboard ship think of that false armistice of World

War I and the hoax that had been played.

Then,

suddenly, after most of the men had left the vicinities of the

ship’s loud speakers, the welcome and almost tragic news

came over the air: Italy had

surrendered unconditionally on the 3rd of September

but the information had been withheld until it would be of the

utmost advantage to the Allied Nations. Welcome news in that it

would make things much easier as far as the quick defeat of Germany

and it’s satellites were concerned but almost tragic in that

it almost gave the Allied forces then on the verge of performing

a very major and serious operation a feeling of over confidence

which well-nigh cost the American and British troops the entire

campaign.

The

Nazi High Command which for years had dominated the whole of Italy had

made it’s plans well. It had probably reasoned that in the

near future it’s junior partners would become tired of being

used as the cat’s paws and would attempt to sue for separate

peace. The steady pouring in of German troops in each of these

countries, until each of these nations could claim nothing their

own, had been carried out to such an extent throughout the entire

Italian peninsula that even the entire native garrisons of that

country were unable to force the Nazis from Italy.

The Germans had planned well to use this once Facist state for

battleground, confident that they could hold it against even the

strongest forces which the Allies could muster to it’s shores.

But back to the PHILADELPHIA and

it’s role in the campaign.

That

broadcast, with all it’s implications, was translated by

many to mean the end of all resistance. The possibilities of attacking

further north, the trapping of thousands of German troops with

equipment and supplies, the dissolution of all of the other Nazi-controlled

states, all these were conjectured upon. Yet, the crew realized

that a fight would still be, for although the Italians might overcome

some of the much hated Boche intruders, it was believed that the

Luftwaffe was still intact and in German hands and would be most

definitely on the wing to stop any large scale massing of ships,

troops or equipment in the Salerno area.

Capri to

the north, the Cape of Salerno just

to the east of that famous island, that long stretch of sandy beach,

a half moon riding high over the lofty mountain peaks, a slight

Mediterranean breeze, but above all, absolute quiet. A picture

to be long cherished were it not that the members of the crew had

their thoughts for the most part far away from the beauties of

nature. A grime task was ahead, a job that kept each and every

man on the alert every second of the time.

That

long period of waiting, watching, hoping and praying again. The

sudden activities of flares dropping over the beach areas, the

quick check on range to the flares with the sigh of relief as it

was learned that they were over 50,000 yards away, the blazing

tracers followed by the heavy ack-ack-fire ashore and then the

heavy rumbling of artillery ashore. Possibly the Italian and German

forces were having a duel of their own for it was a certainty that

no United Nations forces had been landed as yet. Prayers that Badoglio’s

men would come out on top and assure the success of the landings

were murmured. The convoy to the north under heavy air attack,

the crackle of A.A. guns and the crashing of one plane hurtling

thousands of sparks as it exploded just before hitting the water,

the detonations of bombs as they landed, the end of the attack

and the report that no ships had been hit. Crowded into a few minutes

of time, these incidence brought temporary relief to the onlookers

who had ringside seats to the entire show. The ships telephone

circuits buzzed with the various versions of each of these events

as talkers on top side stations passed on the news to their shipmates

below deck.

Those

large explosions ashore, the large fire thirty miles or so inland

off starboard bow, the city of Salerno silhouetted

by the resultant flashes as demolition charges set off throughout

that entire area. Still more gun fire ashore. Phosphorous shells

leaving their white tracers behind as they left the muzzle of the

guns. And yet no firing or sign of enemy activity against the transports

or men-of-war which were creeping ever closer toward the unloading

areas and the shore.

A

slight noise to port and the relief that each man had as it turned

out to be only the dropping of one of the landing craft into the

water. The two hour wait until all boats were ready to form the

first wave and then again that long wait for the boats to reach

the landing beaches. Indeterminable minutes during which all hands

kept their fingers crossed again going through those oft repeated

prayers that those boys heading for the beach would make it safely

and meet with no opposition.

Twenty

minutes to go! The short bursts of machine gun fire in the area

of the Yellow Beach.

The standby to all main battery groups! The cessation of firing

a few seconds later. And again those most welcome of all reports

- landings success - fully accomplished, very little opposition

encountered.

The

joy of all hands as they heard these reports. The beliefs that

all was well and that the Italians, apparently taking the advice

of their new government and it’s requests issued immediately

after the news of the surrender had been announced, had done their

jobs very well and that the Nazi fighting machine was even now

hurriedly running north in a mad rush to clear out of Italy before

the onslaught which was presaged by the arrival of the Allied troops.

The

lack of enemy air attacks was a puzzle which could not be figured

out by most hands throughout the task force. No

calls for fire support from the landing parties was also unfathomable. Things seemed to be moving almost too well. Had

the Italians really done the impossible - chased the Jerries running

back home? Ah well, all good dreams must have endings

and this one was abruptly closed just after daylight on D day when

one of the landing forces requested immediate fire on enemy batteries

which were holding up their advance and consolidation of positions.

With

that first call for help, the real work started. A job that lasted for ten full days for the PHILADELPHIA. Ten days of hell; a short time in a man’s

life but which added at least ten years to the aged appearance

of each and every person aboard that vessel; a period that seemed

unreal and contained so many astonishing and thrilling experiences

that it is hard to believe that only so short a space of time had

elapsed. Reviewed from almost

any angle those ten days brought the war close to every man - jack

aboard that fighting man-of-war, a 20th century war,

a battle not only against the Nazis and their planes alone but

against a more ruthless enemy who had now conceived new and more

potent weapons of destruction.

That

the PHILADELPHIA was

the one “must” item that had to be knocked out of the

way by the German Air Force was very evident when the Luftwaffe

deliberately went out of its way on several occasions to drop their

lethal loads at this vessel. The

surprise of the Axis leaders must have been a great one after this

stalwart ship had been identified, steaming along in the Gulf of

Salerno, still carrying on its regular job of knocking out German

batteries, tanks, trucks, and killing thousands of troops. From

all previous reports, this “thorn of the Sicilian campaign” had

been lying on the bottom of the Tyrrhenian Sea for

many weeks. Passing up those nice, juicy and defenseless

targets in the area and striking only at this vessel, the Nazis

seemed to be determined to get rid

of her at any cost. Repeated

high level, medium flight and dive-bombing attacks were made but,

to no avail.

For

many men the most difficult day of all was the 18th of

September waiting for the five o’clock whistle

and the signal to leave the Salerno area

for a short rest. To others

there was no day which stood out above all others. Each

day during that period was packed with thrills, many incidents

all jumbled together in the cramped recesses of their minds, swiftly

forgotten as new actions occurred, only to be remembered many days

later with the mention of a word, reflections or a passing thought

or action on the part of an individual.

The

consistent firing of the main batteries at enemy shore positions;

the concentrations of tanks blown helter-skelter by the accurate

15-gun salvos; the unobserved firing during the night of the 13th -

14th when more than 4,000 Jerries bit the dust along

a short stretch of road; the attacking planes on the night of the

16th which tried to stop this vessels bombardment on

shore targets and the exultation of the crew as the word was quickly

passed over the phones that one plane had already exploded off

the port quarter and another last seen belching fire as it turned

tail; the hundreds of bombs close aboard; the Limeys swimming over

the side even during the alerts; the passing of those allied bombers

as they winged their way back home and at the exact crossing overhead

the rolling thunderous roars as hundreds of tons of bombs landed

and shook the area for miles around; the burning liberty ship lighting

up the shipping area; that feeling of pride as reports came drifting

in that the PHILADELPHIA had done its job superbly and that its

firing during those terrible days from the 11th to the

14th had done much to save the United Nations’ forces

and forced the Germans to scatter and retreat preventing the Jerries

from pushing our troops back into the area; these were merely passing

incidents and now that the battle is over they take form, each

a separate complete story in itself. Events complete with real action, long periods

of unheard of devotion to duty, hundreds of untold incidents which

would merit awards; but to the crew of this gallant fighting ship

it is the ship - “The U.S.S. PHILADELPHIA” - that is

doing the job.

No

praise was asked during or after any of these campaigns; no time

was spent in counting up the thousands of pieces of enemy equipment,

troops or many installations put out of commission or the devastating

effects the steady bombardments and accurate A.A. fire had upon

the Jerries, not to mention the mere presence of this grand old “lady”. Nor

the serious breakdown in morale that must have followed after the

repeated failures to get this vessel out of the various campaigns. Even today, on this vessel’s birthday,

no symbols emblematic of the enemy planes, tanks, batteries or

guns “knocked off” adorned the bridge or sides of the PHILADELPHIA. We still have a job to do but it is not to

delve into previous records for accomplishments performed, rather

it is to prepare for the future and to get all our equipment in

shape again for that moment when we will again be called upon to

carry on the job.

To

the German High Command possibly it has been an enigma as to why

this fighting vessel was ever named the “PHILADELPHIA”. Although christened after that city, famous

as the home of the Quakers and “brotherly love” this

little spitfire of the United States Navy has repeatedly refused

to act as gentle and inoffensive as her name would imply.

Her

nose still points proudly upward, ready at a moments notice to

head towards the area of battle, her guns stand by waiting for

the signal to train and commence firing, her machinery and other

equipment is ready and when the call comes, this gallant cruiser

will be ready to take its place either alone or with other units

of the fleet in the final task of bringing about the ultimate destruction

of the enemy.

We

sincerely hope and pray that the cessations of hostilities will

ensure us a world again free from the oppressions of the militarists

and let us all live again our normal lives safe in the security

that we may enjoy the freedoms granted us by our Bill of Rights

and that the other nations throughout the world may enjoy the freedoms

contained in the Atlantic Charter.

THE

END

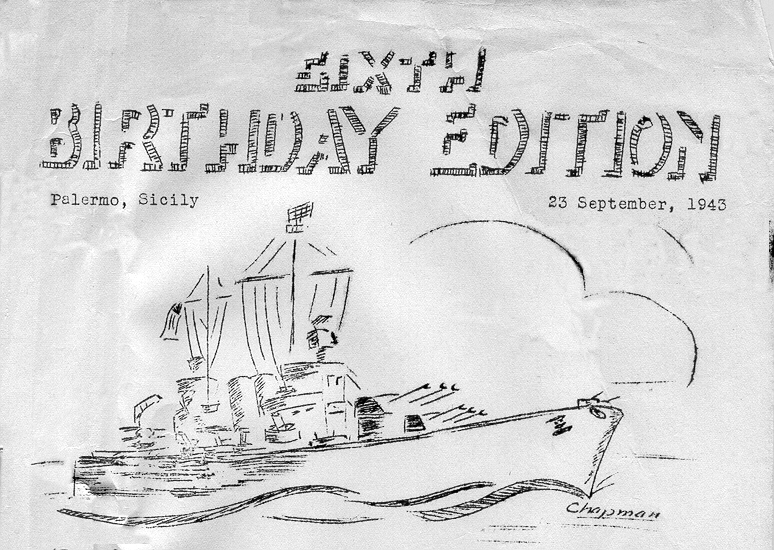

The above text was copied from an original

history in the possession of Ira J. Gardner, son of Ira Leon “Lee” Gardner

who served on the U.S.S. Philadelphia (CL-41) from 1942 to 1945.

All information was copied as it was written (obvious spelling

errors were corrected) and the cover design was scanned and then

inserted in this document. |